Because I’m the kind of vain person who thinks themselves capable of just waltzing into an art festival and setting up their own installation without any relevant qualifications or experience, let me begin by quoting myself: “Here’s a secret about making art: it’s actually really, really easy.”

That’s a line from my interactive, choose-your-own-adventure-style event, “A passage to parallel worlds”, which was part of the 2016 Melbourne Fringe Festival. It might sound pretentious, but I’m going to argue that it’s true.

Art and science seem to be coming together more frequently these days, with good reason. As well as offering a chance to connect with a new audience, art offers a different perspective on scientific concepts. It’s also entertaining, which is always a feature that makes science communication more enjoyable. And conversely, art that makes you think about the world in a new way is extra satisfying.

My event came about through an invitation to present at A Centre for Everything, which is a collaborative program of events led by two Melbourne-based artists. For a while, I’d been trying to come up with a creative way to represent the concept of parallel universes, and this was the perfect opportunity to try something far beyond a straightforward presentation.

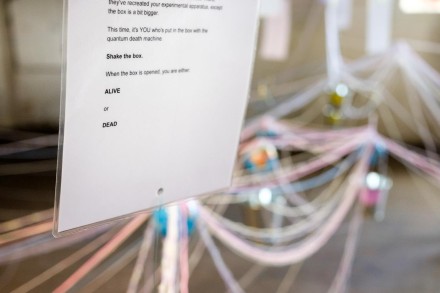

The solution was an interactive story with multiple possible paths, represented in a physical space so the different choices were literally side-by-side. Participants move from point-to-point as they work through the story, which just happens to be about a physicist whose studies involve various theories of the multiverse.

Another artist friend suggested using string to represent the possible timelines, and this is the form it took when repurposed for the Melbourne Fringe Festival: participants carry with them a ball of wool, which they use to trace out their own path through the narrative.

The outcome was a spectacular, tangled representation of the diverging, parallel and sometimes intersecting (at least in this story) paths of potential realities. But aesthetics aside, the most rewarding part was discussing the concepts with participants, some of whom had sought it out—including a few philosophy students, who provided a different perspective again—and some who had stumbled upon it and were intrigued enough to give it a go.

It was also nice to be nominated for an award for Best Live Art, and even though I didn’t win it was still a pleasant surprise and I’m not at all bitter.

Which brings me back to my original contention, which is that art is easy, or at the very least, accessible. Fringe festivals in particular are usually open access, which means anyone can register and put on an event. You do need to find a venue, but in my experience most places are very generous and interested in the science side of things.

It’s a promising trend, and indeed mine was not the only science-themed event at this year’s Melbourne Fringe Festival. Science could be found in comedy, with Alanta Colley’s “Parasites Lost”, and in visual art, with Liquid Architecture’s “Why listen to animals?”

Art can be a fun, intriguing and rewarding way to communicate science. And science communicators are creative souls, so why not give it a go?