Image thanks to Boemski on flickr

I came, I learned, I made a listicle

I’ve been to boot camps that hurt me. Yes, they hurt me a lot. Fortunately, my recent attendance at the Walkely Foundation Digital Media Bootcamp wasn’t in the same category. Rather than aching muscles, I came home with a renewed understanding of how digital media can be used for communicating science.

10 Digital Media Tricks and Tools for Science Communicators: in brief

- Get multimedia happening

- Make the story king

- Know how people read stuff

- Get social. Right now

- Flog that phone

- Search with intent

- Help people find you

- Don’t publish and walk away

- Develop your digital identity

- Keep an eye on trends

Shaping up with Bootcamp: a longer introduction

In 2014 I was fortunate and very grateful to be awarded the inaugural Peter Pockley Grant for Professional Development in Investigative Journalism through the Australian Science Communicators. I would like to thank the ASC for this award, as well as Jim Plouffe from The Lead South Australia (who provided input for my application).

I used the grant monies to attend the Walkley Foundation Digital Media Boot Camp held in Melbourne over November 22 and 23 2014.

Rather than give you a blow-by-blow description of each session, I created a list post – also known as a ‘listicle’ – of useful tips and tricks I picked up. For the record, listicles are one of the most highly clicked on and shared styles of copy (see this post from Copyblogger for more) – something I learned at the course. And they’re easy to read and digest.

The list post appears in brief at the top of this article; see below for more detail on each item. Whether scientist, journalist, blogger, communicator, producer, manager, business leader or student, I hope you find some or all of these points useful.

At the bottom of this article I’ve also provided a snapshot of the program from the Digital Media Bootcamp, and some background information on Peter Pockley.

10 Digital Media Tricks and Tools for Science Communicators: the details

1. GET MULTIMEDIA HAPPENING

Incredible multimedia stories are now published online. The potent mix of words, fixed images, sound and moving footage that made up Guardian’s story Firestorm resulted in a Walkey Award. With interviews, maps, and mountain fly-overs, The New York Times story Snowfall launched a new digital direction for that newspaper, which now has invested heavily in its audiovisual production team.

These two stories required months of work from multiple staff members with diverse skills, and are clearly way beyond the means of most publishing houses (let alone freelance operators like me). But that doesn’t mean you can’t do your own version of multimedia. Small commercial digital story producers, science writers and bloggers can feature layered content to add interest and depth.

Writing a story about a new museum exhibition? Use a stand-alone camera or your phone to take well-lit images – people are great, but unusual objects are also worth grabbing – and use them to break up your text. If you can’t take good photos, go online to find relevant creative commons images on sites like flickr (but do make sure you attribute the photographer somewhere in your article).

“Be sparing with images. The impact is greater if they’re well chosen, relevant and enhance rather than distract from the story.”

Madhvi Pankhania, Producer at The Guardian

What about some sound? Use your phone to grab an audio file that conjures up visions of noisy kids filing in and out of the museum, and immerse it in your article using a program like soundcloud. Audiovisual content is also doable – borrow a friend (or even use the ‘selfie’ approach) to capture footage of yourself walking around the exhibit, or do a vox pop with another person visiting the venue. Perhaps use an App like Vine to make short, snappy, looping clips to add colour and movement to your blog post. (See Item 5 below for how to get best use from your phone for capturing photos and moving footage.)

Online publishing platforms like WordPress and particularly Medium allow writers to easily insert many types of content to support their written material.

“Try to get the pacing right. Ask yourself, ‘do the pictures fit, do they sit alongside the right block of text?’”

Madhvi Pankhania, Producer at The Guardian

Sound, audiovisual and photographic elements can also be added to any social media you create related to the article, and mean that readers are more likely to: (1) visit your article, (2) read your article, (3) share your article and (4) hang around longer on your page (all of which impact on your Google ranking).

2. MAKE THE STORY KING

As discussed in Item 1, the Internet is replete with audio-visual magic. Images, moving pictures, interactive graphs, surveys and sound overlays make digital content snazzy, catchy and eye grabbing. That’s all fine. But it’s close to useless unless underneath it sits a good story. No matter how many additional features you can squeeze onto your web page, the story is still key.

“Multimedia journalism is still journalism – the choice of the story is critical.”

Madhvi Pankhania, Producer at The Guardian

Isabelle Oderberg is Social Media Lead at Australian Red Cross. With extensive journalism and social media experience, she believes the following elements are critical for a good story:

- Make people feel something

- Speak in the right voice

- Have a sense of humour when appropriate

- Know context

- Feed into existing trends.

“Stories that have longevity are worth doing, so pick your topic well.”

Madhvi Pankhania, Producer at The Guardian

It’s also worth remembering that stories posted online attract two types of interest (i.e. clicks) – an initial peak, followed by a longer tail that stretches into the future. Your content does not necessarily have to have an immediate news story-like impact to be worth doing – if you write a quality article that has longevity, it will be found and shared.

3. KNOW HOW PEOPLE READ STUFF

We all complain that we don’t even have time to read our emails, let alone delve into cool-looking articles we find online. You must assume your readers also have this problem.

As a science writer and publisher you must make your content not only relevant, but also easy to find, read and manage. You can do this by:

In essence, writers must help their readers stay in control when confronted with long or complicated articles. This has particular relevance for science, when the content can be inherently complex.

“Subheadings and tags allow people to scan the article quickly and go to the section that they want, and book-mark so they can return later.”

Madhvi Pankhania, Producer at The Guardian

Writers must assume that readers will open articles and perform an initial scroll up and down – usually on a smartphone – before they begin to read. Unless an article is well laid out into sections with subheadings, images and other points of interest, you may lose the reader immediately (see articles like this and this for more on this topic).

“People immediately scroll down to see what the article looks like, to see how it’s formatted, to see if there are comments at the end.”

Front-end Web Developer James Coleman

4. GET SOCIAL. RIGHT NOW

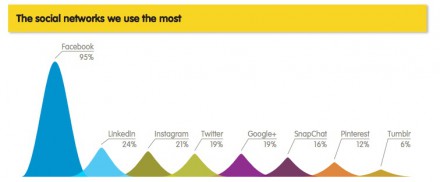

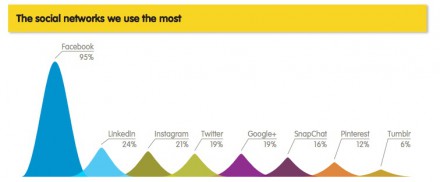

There’s no way around it: social media is here to stay and it’s shaping the way content is created, read and shared (see this recent article: How Facebook Is Changing the Way Its Users Consume Journalism). In Australia, the most commonly-used social media platform is Facebook, with twitter in 4th place and Tumblr in 8th position.

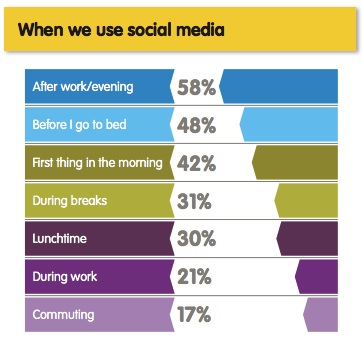

Figure captured from 2014 Yellow Social Media Report

Social media is important not just because it allows you to send out your own material and to converse with people who read it, but because it allows others to share your stuff. And there are ways you can maximize the chances of this happening. Surange Priyashantha (SEO strategist and social media manager at Fairfax Media) relates the following information relating to sharing:

What type of content is most frequently shared via social media?

- Long form content

- Content with images and infographics

- List posts, or listicles (especially with 10, 23, 16 or 24 items)

- Question format, as it drives better engagement: how to? why? what?

- Articles with a byline, because it makes the content more believable

- Content that is chosen to match days and times

(eg video/image posts on weekends, and written posts on weekdays)

Radio National’s Tim Ritchie recommends that short and snappy clips from audio files like podcasts and interviews should be created to use in conjunction with media connected to the long-form content.

“Find the ‘social duration’ – it’s short!”

Tim Ritche, Radio National

As examples, the ‘social duration’ for a 10-minute audiovisual story might be a 3 minute YouTube teaser, or you might chose to extract 30-90 second grabs from a 50-minute audio documentary. These short clips can then be attached to Facebook posts and tweets to maximize rates of click-through and sharing.

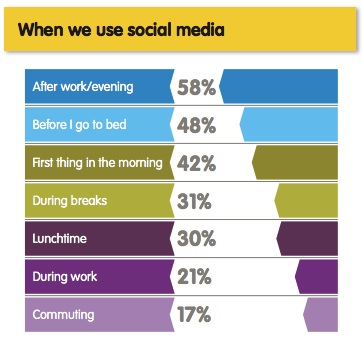

Isabelle Oderberg from Australian Red Cross recommends writers using social media need to think about when people are using their devices to access written content. Articles we read whilst commuting (when we have a large block of time available) are likely to be different from those read during work (when we snatch a couple of minutes here and there). You should think hard about when and how you send your content out.

Figure captured from 2014 Yellow Social Media Report

The only way to know social media is to do social media. Go now. Get started — watch and follow others, think it through carefully, spend time and do it properly. And analyse how each experiment works out – we’re scientists, after all. Look at and apply the data.

Twitter tips from Flip Prior (Twitter Australia’s Partnerships Manager)

- You can now upload up to 4 photos per tweet using the twitter App – simply upload your first image, then click on the small landscape icon again to add further images

- Apply to have the Twitter Verification ‘blue tick’ placed alongside your twitter handle to indicate the authenticity of your identity or brand

- Use Twitter analytics to see organic impressions, view charts of performance, access detailed engagement metrics and export files for reports

- Try not to rely on scheduled tweets. Analysis shows that engagement increases when real people construct and send out tweets in real time.

5. FLOG THAT PHONE

So we know we can jazz up our written material with photos and audiovisual elements (see Item 1). But where can we get such content? Actually, from ourselves. Most of us are carrying around a $1000-$2000 high quality camera in our pockets, and yet we don’t use it to its full potential.

“Why is your phone so useful? It’s always with you, and it’s a good camera.”

Tom McKendrick, Senior Producer Fairfax Media

Tom McKendrick (Senior Producer at Fairfax Media) is full of fantastic tips on how to use your phone as a journalistic tool. Here is a just a portion of what he advised, written in the format of Q&A.

When should I shoot?

- At press conferences

- For pieces to camera

- If you come across crime sciences

- If you witness incidents such as fires, explosions or fights

- To capture vox pops and witness reactions

- When you’re travelling.

How can I best prepare my phone to capture stuff?

- Turn on flight mode to eliminate audio interference

- Always, always, always turn the phone horizontal (‘landscape’)

- Don’t hit record until the view has settled into ‘landscape’

- Plug in a microphone if you can (this might just be a headset microphone, which you can loop over the shirt buttons on your interviewee to get good sound capture from the mouth and chest).

How can I get shots and footage that is well composed and nicely framed?

- Practice what looks ‘right’

- Get to know the rule of thirds

- Let movement happen within your shot, not by moving the camera

- If shooting a person up close, get their eyes in line with the camera, ask them to look into the frame (not out of the shot) and capture their head and shoulders (not whole body).

How do I get the focus and the light right?

- Outside is best for vision; iPhones love sunlight

- A bright overcast day is optimal

- Make sure there is no backlight (i.e. a light source behind the subject)

- Look for lights/lamps/reflection in front of the subject to throw light on them

- When setting up, use finger pressure on your screen to tell the camera where you want the primary focus to be (see this post from Mia Cobb, who has already explained this process very well).

My sound quality is always bad! How can I improve this?

- Get as close as possible to your subject

- Do everything possible to reduce background noise, especially wind – if you can’t get away completely, turn your back to it or put your body in between the noise and the microphone

- Remember that some subtle background noise can add interest (eg traffic, roadworks or wildlife)

- Use a plug-in microphone for best quality. As an alternative, ask the interviewee to hold the phone, or you can use the phone headset as a microphone.

How can I fake it as professional audiovisual camera operator?

- Rule of three: get 3 different angles from the same location: one wide, one mid and one close

- Keep it steady: use 2 hands if needs be, pin your elbows to your hips

- Keep it straight: look at the horizon, and make sure shot is level

- Try not to pan! Compose a nice shot and let the movement happen within it

- If you do need to move, keep it in one plane, keep it slow and know what your start and end frames will be.

Most of all, practice! And invest in editing software if you’re really serious.

6. SEARCH WITH INTENT

Most websites have a search function; that’s fine for basic stuff, and if you kinda already know what you’re looking for. But for detailed research-grade searching, you should be working within Google (or another search engine of your preference).

Did you know you can tell Google to search within a specific url, and to look for particular terms at that site? For example: if you type ‘site:www.asc.asn.au/ intitle:Peter Pockley’ you’ll pull up articles on the ASC website with the name Peter Pockley in the title. More information on how to conduct advanced Google searches is available at Google help. A more general summary of advanced Boolean searching is available here.

“Don’t think that just ‘cause you’re on the internet, searching is necessarily going to be quick. Good research takes time.”

Isabelle Oderberg, Social Media Lead at Australian Red Cross.

You can also ask Google to help you find content published on social media (http://www.social-searcher.com/google-social-search/) and to verify images (http://www.google.com.au/insidesearch/features/images/searchbyimage.html).

Isabelle Oderberg (Social Media Lead at Australian Red Cross) recommends the following online tools to find what people are talking about in real time:

If you can tap into trending topics, you’ll more than likely attract readers. Sometimes this might mean re-editing or re-framing existing content as new moods and trends arise.

It’s also worth keeping in mind that differences exist within individual languages across the globe. In English, key words in Australia might be different from those in the USA (e.g. ‘bin’ versus ‘trash-can’ or ‘footpath’ versus ‘pavement’).

7. HELP PEOPLE FIND YOU

On the flip side of searching is being found. You can do many things to make sure that Google (and therefore readers) have the best chance of landing on your content. Your basic goal here is to make sure that your urls are amongst the top answers that pop up when people search for the kind of science that you write.

Surange Priyashantha (SEO strategist and social media manager at Fairfax Media) advises the following:

How can I make sure I’m found on the internet?

- Use key words that match your content; find these with

http://adwords.google.com/KeywordPlanner & http://www.google.com/trends/

- Make sure your headlines and titles are carefully crafted

- Insert relevant and useful links in your copy (links build your authority)

- If you’re referring to celebrities/famous people, use their full names

- Embed content like tweets into your article

- Increase the amount of time people spend on your pages by making your content attractive (images and graphics) and engaging (put in a poll or a quiz)

- Encourage readers to post comments

- Maximise opportunities for sharing of your content through social media

Imagine a robotic human that is trained to find good stories, and that has a reasonably good capacity to mimic human reading and comprehension patterns: in essence, this is Google. Recent updates to Google mean that it now incorporates semantics. Now searches occur with consideration given to the context of a term within the copy, and whether related terms appear in the same article (see here for more on this).

“Don’t put layers between you and your readers.”

Isabelle Oderberg, Social Media Lead at Australian Red Cross.

The bottom line is this: if you’re creating well-developed written material which uses key words but also more subtle indicators of your expertise, AND you include links to well-known articles and names in your field, then Google will find you.

8. DON’T PUBLISH AND WALK AWAY

You spend days crafting an article or blog post, hours finding the right images and blood, sweat and tears getting the edit just right. Finally, you hit ‘publish’. Done, right?

Nope, not done. So not done. Your content is likely to get lost if you simply leave it to sit on your website at this point. Isabelle Oderberg (Social Media Lead at Australian Red Cross) recommends there are simple ways to ensure your content is found and is interesting over a long period of time (whether over the course of a day, a week, a month or a year):

How can I prolong the life of my stories?

- Choose the topic and related key-words wisely

- Remember there may be a peak and then a longer tail of interest

- ‘Refresh’ the story over the course of the day by adding extra details, embedded tweets relating to the topic (perhaps from celebrities), links to other related content, new images

- Send it out via social media many times: do it manually and with personality, and tweak your language and your hashtags each time

- Find the ‘social flow’ by using social media usage data to work out the best days and times to post material (see Yellow Social Media Report).

9. DEVELOP YOUR DIGITAL IDENTITY

Whether you work in a research institution, for the government or are crammed into a tiny home office as a freelancer, you must develop your own digital identity. Nobody else will do this for you. Your reputation, your visibility and your own personal brand are in your control, and you can easily apply tools that help you to maximise this.

In the book-publishing world, developing your own brand and online identity is often referred to as your ‘author platform’. There are many online articles that address the pros and cons of taking this approach: check out this one from Allison Tait, and another from Brooke Warner.

10. KEEP AN EYE ON TRENDS

Because we work in the science world, it’s tempting to just focus on the hypothesis, research and data side of things. But as communicators we must also stay in touch with cutting edge media trends. I believe science writers need to be able to ‘match it’ with other content generators in order to remain relevant and to maximise the chances that our online content is found and shared.

Isabelle Oderberg (Social Media Lead at Australian Red Cross) mentions two main current trends that journalists must be aware of:

- Multi-screening – the idea that people are usually using more than one screen at a time. For example, TV watchers are often concurrently using their social media platforms to share and discuss content (think ABC’s TV Q&A and associated twitter hashtag #qanda)

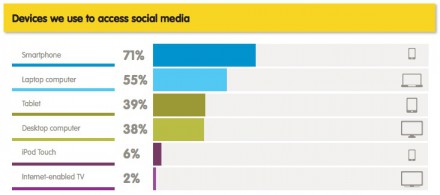

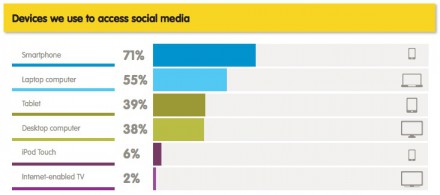

- That soon most — if not all — online content will be viewed via phone screens. For example, of those Australians that access social media, 71% currently do so using their mobile devices.

Figure captured from 2014 Yellow Social Media Report

Many other commenters agree with Isabelle. Double screening appears as one of six emerging trends in media and communications in an Australian Communications and Media Authority article published online by Australia Policy Online recently. The move to mobile is not just restricted to social media, but for all content (see this recent piece All Journalism Will Soon be Mobile for more).

Another important trend is data journalism, or the use of numerical data to create content.

Want to tackle a little data journalism? Try the following free tools:

(thanks to Jack Fisher, UTS Journalism)

Program from the Walkley Foundation Digital Media Boot Camp held in Melbourne over November 22 and 23 2014.

Day 1: Multimedia Production and Online Publishing

Multimedia Storytelling for the Web, Madhvi Pankhania, producer, The Guardian

Data Visualisation, Jack Fisher, UTS Journalism

Podcasting and Audio Downloads: The Whys and Hows of Time-Shifted Content, Tim Ritchie, Editor, Music & Presentation, ABC Radio National and ABC Jazz

Mobile Journalism: On the Road with your Smart Phone, Tom McKendrick, Senior Producer, Fairfax Media

Day 2: Social Media for Getting Stories and Engaging and Measuring Your Audience

Social Media for News Gathering, Developing a Community, and Promoting Your Site and Stories, Isabelle Oderberg, Social Media Lead, Australian Red Cross

SEO Strategies for Content/News Publishers, Suranga Priyashantha, SEO and Social Media Manager, Fairfax Media

Why Journalists Should Learn to Code, and How to Get Started, James Coleman, General Assemb.ly

Twitter Best Practice, Flip Prior, Twitter Australia’s Partnerships Manager – News & Government

Who is Peter Pockley? (taken from the ASC website).

Dr Peter Pockley, a life member of the Australian Science Communicators, passed away in August of 2013. He is widely acknowledged as making an incredible contribution to the field of science communication and scientific journalism.

In 1964 Dr Pockley was the first scientist to work full-time as a science reporter and producer in the Australian media, and became founding Head of Science Programs at the ABC. He established the Science Unit for TV and Radio.

After leaving the ABC, Dr Pockley was appointed Head of the Public Affairs Unit at the University of New South Wales from 1973 until 1989. He then joined the Sun-Herald as a Science and Education Columnist.

As a freelance journalist Dr Pockley wrote for most of Australia’s major newspapers and many overseas, including Nature as Australia’s correspondent.

Dr Pockley established the Centre for Science Communication at the University of Technology, Sydney and was a Visiting Fellow at the National Centre for the Public Awareness of Science in the Australian National University from 1996-2006.

In 2010 Dr Pockley was awarded the Australian Academy of Science Medal; only the seventh winner in its 20 year history and the only journalist to ever receive the award.

Read more about Dr Peter Pockley at ‘Vale Peter Pockley’ in Australasian Science.

ASC members can access a discount for this training by joining the Copyright Agency, which is the major sponsor for the training program. Membership is free and CA members get 25% off our courses and some of our conferences and other events too. See http://www.copyright.com.au/.